A PHILOSOPHICAL APPROACH FOR CREATING A NATURE-INCLUSIVE LIVING ENVIRONMENT

Philosophy and the environment

Philosophy and the living environment have always been inextricably linked. The Greek origin of the word “philosophia” – the love of wisdom – reminds us of the fact that philosophy as we know it today originated in the city-state of Athens. The city where Socrates questioned people endlessly on the street. Philosophy and the living environment are not only connected because philosophy was born and developed there; without the framework of a living environment philosophy could not exist.

Athens formed the thought of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle; and the liberal Dutch cities played a crucial role with the emergence of modern philosophy that arose from the Rotterdam of Erasmus, the Leiden of Descartes and the Hague and Voorburg of Spinoza.

Philosophy cannot be seen in isolation from the context of its environment. Ideas do not operate in a void; they respond to and depend on people and their environment. It is the living environment where different people and ideas come together and clash. There is therefore a mutual influence here: philosophy is the living environment and the living environment is philosophy, both united in man. The living environment is – just like humans – always evolving and can therefore be seen as an organism.

The city as a body without organs

Regarding the living environment as an organism is a powerful image that has long gripped urban planning. Richard Sennett, an American labor sociologist, dates the idea of the city as a hierarchically organized body back to William Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation in 1628. Urban planners have since been obsessed with creating the city as breathable, hygienic organisms where blood (the individual) is free can circulate in blood vessels and where waste products are treated by the designated organs. Where an organ does not work properly, there is a problem – just like any other organism. And at this point our lungs almost disappeared.

The disappearance of the lungs of the city

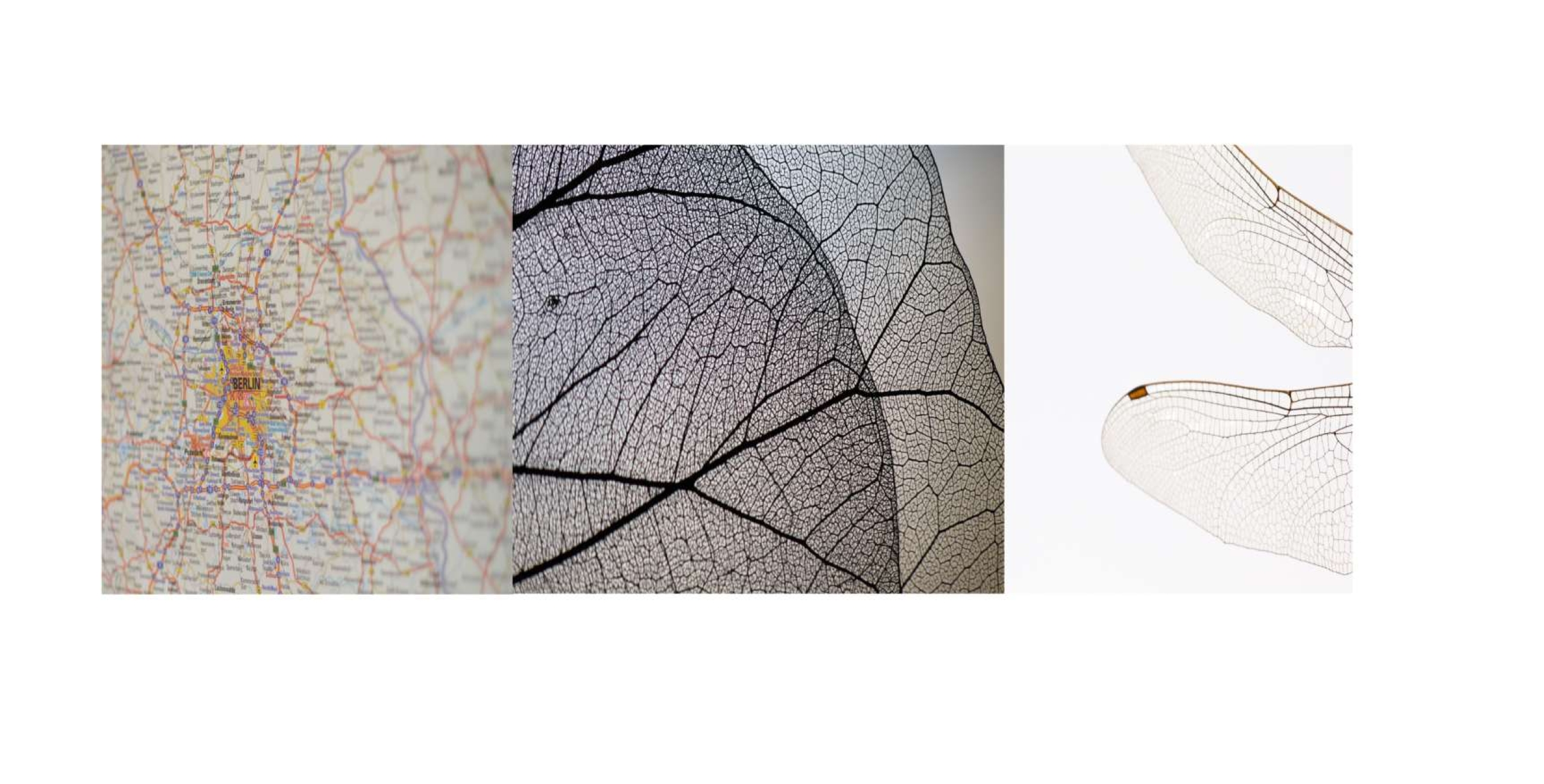

Since the early beginnings of urban planning, man has been copying nature; after all, with her apparent timelessness she has learned to perform each of her tasks as efficiently as possible. For example, the functionalistic logic of perfect (blood) circulation can be seen when you put an image of a wing of an insect, a leaf of a tree and the map of a city side by side.

However, something changed in the late eighteenth century. Cities grew to unprecedented dimensions, becoming centers of pollution, poverty and deprivation. Explosive industrialization has replaced forests with factories faster than ever, and what was once clean air has been replaced by the smell of smoke. This transition had its parallel in philosophy.

Where once man and nature were inextricably linked, nature was now degraded into just a product, a raw material. The immediacy of nature was lost. The exponential growth of industrialization was accompanied by tremendous growth in natural science. The deepest effects of nature have been investigated and ascertained. Instead of approaching nature in an organic, holistic way, natural science was methodological. Isolated individual appearances were taken out of context and observed. Exemplary for this is the philosopher – and initiator of modern natural science – Francis Bacon, who argued that if we want to arrive at practical and useful knowledge, nature must be put on the rack. In other words, to make progress, man must dominate nature. To this day, this philosophy remains the predominant way of thinking, both inside and outside the natural sciences.

It is beyond dispute that the advancement of natural sciences has brought us, as humanity, an incredible amount of knowledge, but this came with a price: an even further alienation from nature. Now more than ever, man observes nature as something outside of himself and forgets its dependence.

Creating a positive feedback loop

Due to our alienation, we ended up in a negative feedback loop. The decrease of nature in the living environment causes alienation, which in turn results in a decrease in nature in the living environment.

The implications of the lack of both the physical presence and the human appreciation of nature are becoming increasingly tangible. Never before did we experience this amount of flooding/drought, heat stress and air pollution in our living environment. In a way, climate change makes our dependence on nature painfully clear. And that clarity is exactly what we need for a paradigm shift.

Remedying our alienation from nature is no longer just a cultural issue, it is now also a problem that threatens the survival of society as we know it. The solution is very simple: creating a positive feedback loop.

By adding more nature to our living environment, we experience the positive effects of it: flooding and drought will occur less, the temperature will be more pleasant, the way to work more enjoyable and the amount of CO2 that ends up in the atmosphere becomes less. As a result of these positive effects, there will be a revaluation that will lead to a “virtuous circle” or a positive feedback loop in which we will jointly add as much nature as possible to our living environment and rediscover our place in nature.

Creating the positive feedback loop has to start somewhere, unfortunately there is no fixed recipe for radical innovation. Changing the environment and thereby changing our thinking can feel uncomfortable. Someone must support the pioneers within organizations and ensure that they are not alone. That someone is BLOC. We are not only committed to creating Next Generation Cities but also to a new way of thinking.

Within BLOC I am committed to contribute to a nature-inclusive living environment.